The Moral Circle

Our daily lives are full of moral decisions. For example, what should I buy at the supermarket? What is the best way to get to work? What clothes should I buy? And so on. These decisions affect not just hundreds, but thousands of individuals involved in their creation, transformation, use, and consequences. So, what should we do? Should I buy the meat or the vegetarian product? Should I drive to work or take public transport? Should I shop at a sustainable store or a fast-fashion store? While these decisions are clearly shaped by our socioeconomic class, they are also influenced by broader normative values and beliefs.

One of the metaphors used to illustrate these criteria of moral relevance is the moral circle (see my review of The Expanding Circle, Ethics Evolution and Moral Progress), which suggests that our circles of moral concern have expanded over time, from those closest to us (including family and loved ones) to those farthest away (including insects, plants, and other entities to which we normally pay little attention). More and more individuals have thus been included in these closer circles. For example, we care for our pets, although this may be for various reasons (see here my review of Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat). We are also increasingly considering entities in our more distant circles, such as plants or even AI.

The closer we get to the limits of our moral considerations, the more questions arise. For example, do plants have the same moral relevance as insects? What value should I attribute to an ant in my daily moral decisions, and how does this compare to the value I attribute to a fly? And compared to an elephant? These questions are further amplified when we consider the material basis of entities that we deem worthy of moral relevance. Should carbon-based entities be given greater moral recognition than (potential) entities based on other materials, such as silicon? We may also question their temporal basis: do future carbon-based entities, or silicon-based ones, have the same moral value as current entities (ceteris paribus)?

Clearly, our moral intuitions come to the fore, prompting thoughts such as: ‘Ants, robots and LMMs have no place in my moral considerations. They don’t feel, experience or have consciousness. The same can be said of things or beings that do not yet exist. In short, they do not matter.’ However, these intuitions reveal a morally obtuse nature that often strays from the realities and implications of our actions. It is informative and useful to establish and develop conceptual tools that clarify our actions, whether they concern silicon-based entities or living beings that are evolutionarily distant from us.

This is precisely what Jeff Sebo sets out to do in his book, The Moral Circle. Across seven chapters, he sets out the key arguments for considering moral entities that are furthest from our empirical moral cores, including those we normally ignore and those that may or will become moral agents in the future. He outlines the basis for establishing moral recognition (Chapter 1) and the normative implications associated with this moral recognition (Chapter 2), while assuming the scientific and moral uncertainty that always characterises these domains (Chapter 3). He also considers possible, different or future moral agents (Chapter 4), both individually and collectively (Chapter 5), and the reality in which we find ourselves immersed: an outdated cognitive system that does not fit with the environment we have created (Chapter 6). He concludes by providing reasons why human supremacist exceptionalism must be rejected, based on this same human exceptionalism, as special agents capable of harm, but also capable of bringing about change.

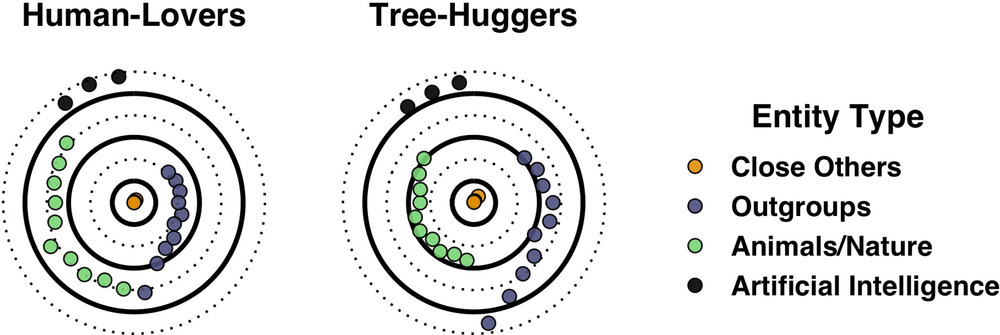

Our empirical moral circles differ greatly from the main prescriptive proposals. Various empirical studies suggest that our moral attention is not only diverse in terms of who we ask (highlighting aspects such as age, gender, nationality or even political preferences), but also in terms of which entities we consider relevant. Some people consider that, after their family and friends, the next entities worthy of moral consideration are other members of the human species with whom they do not usually identify (members of the outgroup), followed by animals, natural entities, and finally AI. However, others seem to conceive of a different hierarchy, placing animals and plants in the intermediate circles after members of the ingroup, followed by members of the human species from the outgroup, and finally non-carbon-based entities (see Figure 1 in (Rottman et al., 2021)).

This wide variability in the entities we consider in our most immediate moral circles can be explained through three aspects: (1) Which entities have moral status? (2) What real differences determine this theoretical moral status in our moral practice? (3) Why do we act the way we do?

Beginning with the question of moral status, Sebo devotes much of Chapter 1 to discussing the reasons typically used to account for an entity’s moral status (Sebo, 2025, p. 15). He discusses the idea of intrinsic value, i.e., that they are important in themselves, as well as the existence of certain common characteristics, such as sentience, and the fact that certain duties are owed to them. In other words, they are moral patients, and certain moral agents act upon them, causing change for the better or worse. However, whether or not they have the possibility of recognition of such moral status, these reasons are glimpsed in a second, more general aspect, namely, the clear distinction between moral theory and moral practice. That is, the distinction between what qualifies as a moral and right action, and the general moral obligations that arise from this, versus how we make good moral decisions in our daily lives (Sebo, 2025, p. 30).

However, as I see it, this perception of moral status and the often precarious leap between moral theory and practice merely reflects a third modulating factor: our out-of-step moral nature (Sebo, 2025, p. 99). This perception of our moral nature has been a recurring theme in numerous discussion forums, giving rise to prolific debates about what should be done, e.g. in transhumanist debates (Persson & Savulescu, 2010), and what is being done, e.g. in debates on behavioural economics and choice architecture designs involving nudges, (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Thus, our moral, lay, and popular understanding of the world, which serves us well in our everyday moral practice, does not align with the true implications of our moral actions. Clear examples of this can be seen in our perception of global warming (‘I do not see the direct consequences of my actions, therefore they do not exist’), our consumption of meat (‘I do not see the suffering, therefore it does not exist’), and even more mundane aspects, such as the attention we pay to products visible in supermarkets (remembering the nudges mentioned above).

However, this nature should not restrict our actions or moral duties to the canon. Rather, it should account for limitations and provide a starting point for action. If we recognise that certain moral patients (or potential moral patients) are at stake, and if we can justify their moral relevance, then we can prescribe desirable courses of action.

There is clear evidence of the physical characteristics that make many non-human entities important. In other words, we have empirical certainty that triggers certainty in values and reasons to attend to the well-being of such entities from different ethical paradigms — consequentialist, deontological, or virtue-based. However, it is also evident that, in many cases, we are working with double uncertainty (Sebo, 2025, p. 46): one concerning values (i.e,. which characteristics or aspects are valuable or sufficiently valuable to consider entities as moral patients), and the other concerning facts (i.e., which entities actually have the valued characteristics). Nevertheless, this should not prevent us from advancing the moral discussion. We can address this uncertainty by adopting Sebo’s Principle of Risk:’[…] all non-negligible risks — that is, all risks that have a decent chance of happening — merit consideration in our decisions’ (Sebo, 2025, p. 48). This would adopt an inclusive approach to the factors that determine moral consideration. Furthermore, as Sebo himself acknowledges it is better to be safe than sorry, even if we are ultimately proven wrong (Sebo, 2025, p. 52).

Despite the empirical and moral uncertainties involved, Sebo revisits the issue and proposes conceptual tools with which to address these potential moral agents. One of these is the Principle of Harm Reduction. According to this principle, Sebo argues that ‘we should avoid harming others unnecessarily, and if we do cause harm, we should help those affected to recover where possible. We should also cultivate habits, relationships and other structures that support this work’ (Sebo, 2025, p. 31). This principle allows us to respond to the limitations or complexities of theoretical-normative application in everyday practice, as it is consistent with different theoretical ethics.

Furthermore, subsequent reformulations of this principle allow us to account for uncertainty about the correct action to take in the face of entities that we doubt have characteristics that make them worthy of moral recognition. From an exclusionary perspective, entities with moral status necessarily have consciousness, sentience, and agency. However, more inclusive positions would reduce these necessary criteria to sufficient ones (Sebo, 2025, p. 18) or expand them to looser definitions of consciousness, sentience, and agency (Sebo, 2025, p. 69). According to this principle and other considerations, such as a precautionary approach, we should take these entities into account and help them whenever possible, even if we are not the agents causing harm. This principle also applies to entities that are not yet moral agents, such as future generations of human and non-human animals, or potentially non-carbon-based moral agents, such as robots or LLMs. Along with other considerations, such as a precautionary approach or the principle of equal consideration, this principle dictates that we should take these entities into account, even if this leads to differential treatment (Sebo, 2025, p. 37).

Since the beginning of the book, Sebo argues about which entities deserve to be considered morally, advocating for an almost exponential expansion of the entities that, according to his argument, deserve to be considered. However, if we assume that all entities that might matter actually do matter (under the Principle of Risk) and that we should do everything we can to reduce their suffering (under the Principle of Harm Reduction), are we, in attempting to consider all these entities, losing our recognised and certain interest in current actual entities by attributing it to possible and/or future entities or agents? Sebo addresses this question/objection in chapters 3 and 5, suggesting that this idea of ‘merit consideration’ is not radical, but rather that it should be considered ‘whenever possible’.

One way to build on this broad consideration is through co-beneficial interventions, which benefit both current moral agents (who therefore have the incentive to implement them now) and present and future moral patients. While the practicality of such interventions may be evident, e.g., state-led initiatives to reduce food waste by giving away chickens, thereby raising awareness and promoting civic education about these animals (Sherriff, 2025), two potential limitations emerge. Firstly, many of these interventions are framed as voluntary individual decisions (e.g., buying plant-based products instead of meat). Secondly, the effectiveness of this type of intervention, which involves relatively minimal effort on the part of moral agents, tends to be much lower than other interventions that, while not individually co-beneficial, are widely effective, e.g. compared to co-beneficial nudges aimed at reducing water consumption by comparing it with that of neighbours or generating infrastructure that allows for more prudent use of this resource, even if this implies some individual restriction, (Chater & Loewenstein, 2023).

For this reason, I believe he also places importance on developing certain virtues and character traits that align with this more civic-minded approach to life. Concluding his book, Sebo presents a somewhat optimistic view of human exceptionalism and the future of humanity. In the final pages, he states: ‘[…], our species is still at an early stage in its education and development. We thus have both a right and a duty to prioritise ourselves to an extent, because we need to take care of ourselves and invest in our education and development. However, if and when we develop the ability to devote a majority of our reserves to nonhumans sustainably, we might have a duty to do so at that point. And if we help nonhumans as much as possible along the way, then we might be more likely to make this altruistic choice when the item comes” (Sebo, 2025, p. 129). Metaphors like this, in my opinion, point to an education that focuses on virtues and character traits. This kind of education helps us to establish action that benefits everyone, while also creating positive political, social and specific infrastructures (including LLMs).

In short, Sebo illustrates in this book that morality is a marathon, not a sprint (a phrase he references several times throughout the text) by outlining the necessary tools and justifying why we should consider entities that are typically either beyond the empirical limits of our moral consideration or outside of it entirely. Sebo sets out the criteria that we can use to recognise and consider entities that are worthy of moral attention right now (even if there may be some uncertainty), as well as the work towards the moral consideration of those entities that may have moral status in the future.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Martín R., A. Daniel (2025). Review of “The Moral Circle”. https://danielmartinruiz.com

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{ martín r.2025the-moral-circle,

title = { Review of "The Moral Circle" },

author = { Martín R., A. Daniel },

year = { 2025 },

url = { https://danielmartinruiz.com/books/sebo_moral_circle/ }

}

References

2025

- The Moral Circle: Who Matters, What Matters, and WhyMay 2025

- The European towns that give away free chickensBBC Future, Mar 2025

2023

- The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astrayBehavioral and Brain Sciences, Mar 2023

2021

2010

2008

- Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and HappinessMar 2008