Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat

It is not easy to think straight about animals. We are a fickle bunch, and our opinions of them are often divided. Sometimes we find them cute, other times they disgust us, often they terrify us, and countless times we find them tasty. But what causes this diversity of attributions of value? One obvious reason is that they are different species and therefore treated differently. However, numerous texts argue that this is not a compelling reason to treat different entities differently, even from an ethical point of view (see, for example, Animal Liberation Now). Even towards members of similar but different species, which we know to be very similar, our behaviour is completely different. Take wasps and butterflies, for instance. We don’t treat them the same way. The same goes for pigs and dogs. They are clearly different species, yet we know that there is no particular difference in terms of their capacity for suffering and general cognitive ability. So why do we conceive of them as two almost ontologically unequal entities?

This ‘something’ that leads to such different treatment can be seen in our day-to-day behaviours (like what we eat), professional behaviours (for example, using animals as a way of making products or as the product itself), and academic and research behaviours (such as the different studies carried out for learning and scientific purposes). Hal Herzog, in his book Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals’, recounts the myriad forms of interaction between humans and non-human animals. He takes an in-depth look at this complicated relationship to explore the factors that determine our animosity, passion, detestation or indifference towards these entities.

In his opening chapter, Herzog provides context by describing various situations that illustrate our complex relationship with animals. These range from the categorisation of what constitutes an animal, which challenges phylogenetic taxonomies in order to avoid feelings of guilt, to the decades-long relationships of affinity between manatees and their carers. Herzog explains that all these relationships can be encompassed within an interdisciplinary field known as anthrozoology. As the name suggests, this is the study of human interactions with other species (Herzog, 2021, p. 2). The aim of this science is to uncover the reasons and factors that motivate and modify our actions and relationships towards animals.

Throughout its ten chapters, Herzog recounts a variety of perspectives on this discipline. These include how personality can influence the types of pets we choose (Chapter 1), the immediate and potential ultimate reasons for owning pets (Chapters 2 and 3), the moral inconsistencies of dog breeders (Chapter 4) and cockfight breeders (Chapter 6), as well as individual differences such as gender (Chapter 5) and evolutionary differences like our preference for meat. The book concludes with a realistic view of our nature and treatment, and why it is often unclear and inconsistent. Below, I present some notes and sections that I consider most relevant to our moral project.

When we think about how we treat animals, we often see things that don’t seem right. We wonder why these things are happening. These can be analysed through the prism of proximate and ultimate causes or reasons. Proximate causes explain how a phenomenon occurs; that is to say, the mechanisms or reasons that trigger our relevance towards certain animals or our indifference towards others. Ultimate causes, on the other hand, account for the existence of such actions, explaining why or for what purpose they occur.

Among the proximate causes that determine the differential treatment we give to different types of animals, alongside other causes, may be their physical appearance and how pleasing they are to the eye, or ultimately, whether they are cute. Throughout philosophy, beauty has proven to be a more prevalent factor in moral judgement than one might wish. Immanuel Kant, for example, believed that beauty and goodness existed in separate spheres of judgement. However, beauty could somehow predispose moral judgement. In the Critique of Judgement (Kant, 1987), Kant explicitly develops this idea, explaining that the experience of beauty predisposes the mind to receive moral law: ‘The disposition of the mind produced by the contemplation of beauty favours moral sentiment.’ (KU, § 59). However, he goes on to explain that this predisposition cannot form the basis of morality: ‘The beautiful does not provide any concept of morality, nor does it serve as a foundation for it’ (KU, §59).

If we think about the clearly differential moral relevance we give to a moth and a butterfly (see, for example, the graphic results of study 2 of the Animal Dilemmas project).

But just because something is unethical does not mean it is not done. We continue to think of cuteness as an essential part of how we behave. Various studies have linked this aesthetic trait to the ‘cute response’, a reaction that evokes a similar feeling to that experienced when seeing human infants. This reaction of tenderness and beauty has been widely used by major animation studios such as Disney in the ‘babyfication’ of animated animals, awakening not only anthropological traits in us, but also feelings of cuteness. The impact of these depictions has been so significant that it has led to changes in policies on hunting baby seals (Charlemagne, 2009), with widespread support from the general public (International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), 2024).

Aesthetics and physical appearance are fundamental to our moral criteria, but they are not the only factors. After all, we are not one-dimensional entities. Other aspects, such as use (if they have any), culture or society, can also affect our moral judgements and, therefore, our relationship with such animals. Arnold Arluke, co-author of Regarding Animals: Animals, Culture and Society with Clinton Sanders and Leslie Irvine (Arluke et al., 2022), calls this interaction the sociological scale. This scale demonstrates that, despite being on the same phylogenetic scale, dogs and rats are distant on a sociological level. Aspects such as gender, age or nationality are key to understanding this interspecies relationship. What is considered a pest in one culture may be considered a pet in another. It is worth briefly mentioning the debate that Herzog presents on the word ‘pet’ itself here. Some activist movements advocate replacing the word ‘pet’ with ‘companion animal’. The word ‘pet’ implies ownership, whereas ‘companion animal’ implies, at the other end of the relationship, a guardian or companion (Herzog, 2021, p. 64). We will use both terms interchangeably.

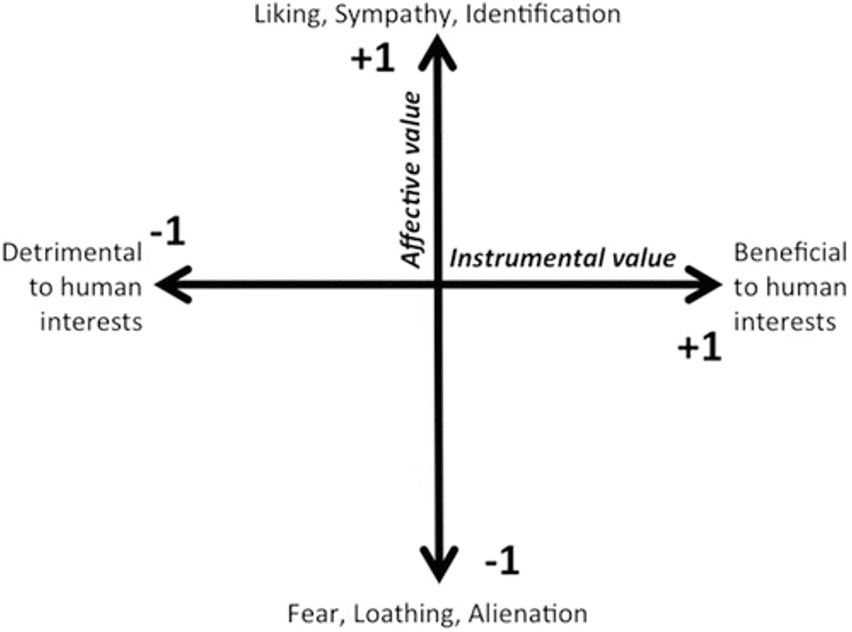

Attitudes can be described in terms of three subcomponents (Herzog, 2021, p. 248): affect (how A makes me feel emotionally); behaviour (how that effect is reflected in my actions); and cognition (what I think about that thing). These components do not necessarily have to be aligned. James Serpell has created a matrix that partly accounts for our professed attitudes towards different animals (Serpell & Hsu, 2016), particularly their affective and cognitive value, and how this can be transformed into affective value (see Fig. 1, from Serpell, 2016). Serpell believes that our attitudes towards animals can be reduced to two dimensions. The first dimension relates to affective attributions towards species, ranging from love, sympathy, and empathy to fear, disgust, and dislike. The second dimension relates to usefulness to humans, ranging from human benefit (e.g. livestock or the use of animal products) at one extreme to harm to human interests (e.g. pests or the transmission of diseases between species) at the other. This matrix can account for the following categories of animals: (1) Those we love and are not very useful (such as companion animals). (2) Those we do not love but are useful (such as certain farm animals). (3) Those we do not love and are not useful to humans (such as pests). (4) Those we love and are useful (such as certain medical assistance animals, to which Herzog also devotes a section in chapter 2 and to which anthrozoology generally attaches considerable importance).

While there are many reasons why we are drawn to or put off by certain animals, we should also consider why we keep pets in general. In Chapter 3, Herzog addresses this question by appealing to ultimate causes. He seeks to analyse whether the benefits of having a pet are sufficient for us to maintain it throughout evolution. From an evolutionary perspective, companion animals are problematic, as they require a significant investment of time, energy and money, despite us not sharing any genes with them. Some hypotheses are that pets offer unconditional love (Herzog, 2021, p. 70) and generate a greater sense of health or promote healthier lifestyles (Herzog, 2021, p. 73). Although there is some evidence to support these outcomes, there may also be spurious correlations.

Humans have kept pets for approximately 35–40 thousand years. What has made this practice continue? Two of Herzog’s theories relate to some of the proximate causes we presented above: the possibility that pets are parasites and the possibility that they are mental viruses.

In recent decades, the number of companion animals has grown both nationally (RTVE.es Noticias, 2025) and internationally (NAR Economists’ Outlook, 2024). Could domestic animals be exploiting human evolutionary mechanisms of parental care by activating certain evolutionary prompts similar to those activated by human infants? In this way, companion animals reap significant benefits, such as protection and food, by exploiting this instinctive reflex at the expense of human resources (Kubinyi & Turcsán, 2025). Just as our interest in music arises as a side effect of how our brains are wired, could this also explain our relationship with companion animals in terms of our tendency to care for them? Are we misfiring our evolutionary efforts? Another theory that Herzog considers is that pet ownership is nothing more than a mental virus that has remained stable over time. Like memes, the units of cultural transmission, pet ownership could function as a proxy for caring for certain entities and considering them as part of the social norm. Just as a Catholic family will raise their child in the Catholic faith, and that child will likely also become Catholic, a family with a pet will raise children who will likely have pets as adults. This cultural explanation could account for how quickly norms can change, such as the mass ‘euthanasia’ of pets before the Second World War in the United Kingdom in 1939, or the diversity of pets across different cultures.

Whether they are social memes, viruses or parasites, it is clear that our relationship with animals is complex. But is it the same for everyone? In Chapter Five, Herzog recounts the real and apparent differences in how animals are treated based on gender. These differences between groups can be analysed from an anthropological perspective. It is sometimes said that women are more involved in animal rights than men. After all, women and animals are both victims of oppression. Furthermore, it is generally observed that men tend to abuse and be more violent towards animals, while women tend to be more involved in the animal rights movement. But does this imply a gender difference in the treatment of animals? Evidence suggests that there is greater variability within groups than between them, i.e. there are more differences in the treatment of animals among men and women than clear categorical differences between the two groups. However, even small intergroup differences can have significant effects on extreme trends due to the interaction of politics, culture and evolutionary factors. Herzog advocates an explanation based on bell-shaped curves and normal distributions.

Normal distributions are present in many psychological and physical phenomena, such as intelligence and height, respectively. While the differences between men and women in these characteristics are generally small, at the extremes of the curve, these slight differences can result in significant variations in the ratio. According to Herzog (Herzog, 2021, p. 147) himself, ‘My position is that many human sex differences, including how we treat animals, are simply the consequences of an elegant statistical principle that even most psychologists don’t understand. It is this: When two bell curves overlap, even a small difference in the average scores of the two groups produces significant differences at the extremes.’ Small differences between the averages of men and women in certain traits can have a significant impact at the extremes. For example, if the distribution of the trait “liking animals” is bell-shaped, most people will be in the middle, but a small proportion will be at the extremes, either liking animals very much (activists) or disliking or hating them (abusers).

Assuming the bell curve is correct, the differences between the pro-pet and anti-pet extremes become greater the further we move from the centre. This could explain why there are more women at one extreme and more men at the other, despite studies showing only minor differences. See interactive figure 2 to see how a small difference in the mean can lead to significant changes in the ratio at the extremes.

Rather than offering explanations based purely on arguments (which can sometimes lead to unintended consequences or put us in a bind) or on impulsive or intuitive criteria (which can be changeable and sometimes harmful), Hal Herzog provides a non-moral analysis of our relationship to other animals — or at least one that differs from the approach usually taken by philosophers and ethicists. There is often a gap between more humanistic disciplines, such as prescriptive ethics, which analyses the reasons that demand the moral and legitimate use of different animals, and more descriptive sciences, which, although they investigate descriptions of animal capacities and aspects, do not offer or explain moral courses of action.

Herzog addresses the gap between prescriptive action and the evidence that may determine this action. In his final chapter, he illustrates this perspective by presenting a pragmatic and realistic (and, in my view, reassuring) vision of human beings and their (often inevitably moral) relationship with animals. Rather than adopting the perspective of a philosopher or someone who can be found at one of the aforementioned extremes, Herzog presents the viewpoint of an average individual, such as Judy Muzzy, the owner of a hair and nail salon who, in her spare time, rescues endangered turtles and monitors their delicate hatching process. This example confronts us with clear, and sometimes harsh, evidence that very few people are 100% consistent and committed to their principles. However, there are hundreds or thousands of people like Judy who do what they can in their own small corner of reality and who are, to varying degrees, concerned about our often complicated and paradoxical relationship with animals. This revisits what John le Carré conveyed when he said, ‘The fact that you can only do a little is no excuse for doing nothing’ (Herzog, 2021, p. 275). The contradictions that flood our daily lives in our relationships with animals (among other things) are not anomalies or hypocrisy, but rather inevitable evidence of our humanity.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Martín R., A. Daniel (2025). Review of “Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat”. https://danielmartinruiz.com

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{ martín r.2025some-we-love-some-we-hate-some-we-eat,

title = { Review of "Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat" },

author = { Martín R., A. Daniel },

year = { 2025 },

url = { https://danielmartinruiz.com/books/herzog_some/ }

}

References

2025

- Las mascotas superan a los niños, el gran cambio en los hogares españolesJan 2025Accessed: 2025-12-02

- From kin to canines: understanding modern dog keeping from both biological and cultural evolutionary perspectivesBiologia Futura, Jan 2025

2024

- Survey reveals: Citizens clearly support EU ban on seal productsAug 2024Accessed: 2025-12-02

- A stunning stat — there are more American households with pets than childrenAug 2024Accessed: 2025-12-02

2022

- Regarding Animals: Culture and SocietyAug 2022Revised and updated edition

2021

- Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About AnimalsAug 2021

2016

2009

- Hunting cute baby seals: Europe’s hypocrisyMay 2009Accessed: 2025-12-02

1987

- Critique of JudgmentMay 1987Cited section: § 59